Turning the Focus From Human to Nonhuman Actors

Interview by Tatuli Japoshvili

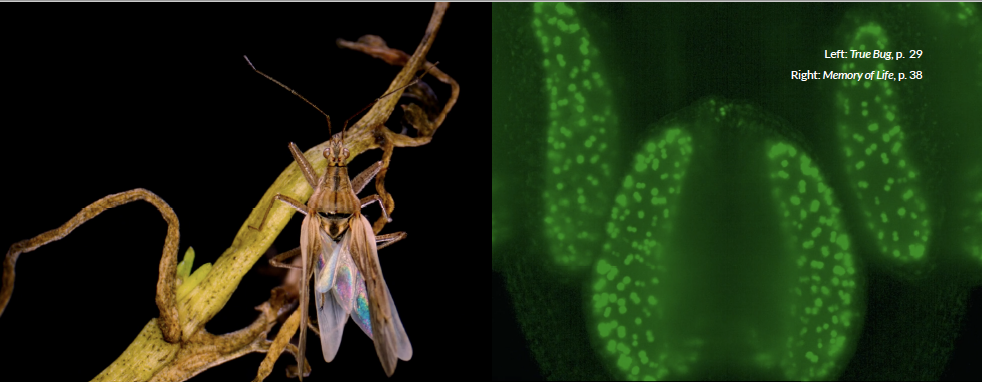

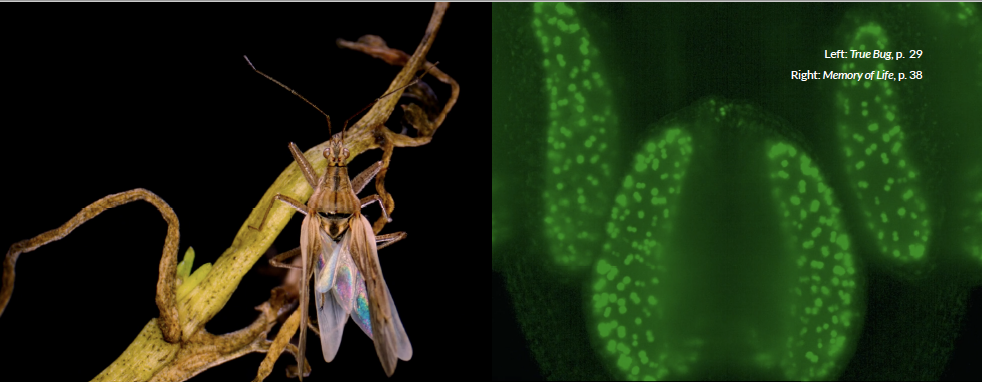

True Bug by Tuisku Lehto and Memory of Life by Juhani Haukka take a different perspective from the typical documentary film. These two works step aside from human narratives and instead focus on the connections between human and nonhuman subjects. Nordisk Panorama Film Festival’s Tatuli Japoshvili spoke to the filmmakers about the engaging visual storytelling of their films.

TJ: First, I want to pay attention to depicting the connection between human and nonhuman actors in your films. Tuisku, as I experienced it, your film True Bug starts with a familiar documentary film setting but gradually turns itself into something unexpected, peculiar and fun. You construct a speculative reality in which the experiences of being human and being an insect enmesh. What made you think about the connection between humans and insects?

“Nonhuman species also have interesting things going on in their lives. And why tell stories only about humans?”

TL: Everything started from encountering bug enthusiasts during the holiday trip I spent in Hanko. For me, it was very moving that while every single tourist was taking pictures of buildings, the sea and the human environment, the enthusiasts were looking for insects called True Bugs. Before this trip, I already knew about the Japanese dance Butoh — a practice in which it is believed that, while performing, a human being can turn into something else. The dancer I found told me that insects in Butoh are considered teachers. I wanted this belief to appear as one viewpoint in the film. The idea of the film is also inspired by childhood memories from when it was easier to relate to species other than humans. Nonhuman species also have interesting things going on in their lives. And why tell stories only about humans? Also, I wanted to challenge an antagonistic attitude humans have toward insects. Once we get familiar with their world, we start noticing their beauty.

TJ: Juhani, in your film Memory of Life, you follow epigenetic research about the astonishing Thale Cress plant. The narrator of the film talks to the plant directly, expressing how much humans could learn from nonhuman species. How did the idea of making the film appear?

JH: I have a professional background in the history of sciences and psychohistory and I have always been very interested in the topic of memory. I came up with the idea to put the Thale Cress plant in focus and to explore the process of remembering after reading an article about various groundbreaking scientific experiments done on the plant. One of these experiments was dedicated to researching memory. I started contacting biologists and found out that there is quite a big scene in Finland. There was a worldwide seminar in Turku where hundreds of scientists came to the city to discuss this topic. The discussions held there helped me to realise that by focusing on the plant and exploring the process of remembering through it, I could talk about contemporary ecological situations and the need for rebalance.

TJ: At one point, the female voice in your film says: “I look at you — in this world of endless intertwinings — which escapes any single story”. Here, you allude to the agenda of anthropocentric thinking in which the history of humanity, as we inherited it, is precisely a “single story” of a human. In the film, you also include archive clips which depict human history. However, you decide to show them very fragmentarily, so that the history they initially represented loses its importance. What was your approach to the archive tapes and how are they connected to the Thale Cress plant?

JH: The whole idea of the film was to rethink the relationship between humans and plants by centralising the Thale Cress. At the same time, I did not want to exclude humans from the story but rather to place them on the edge of the film. I was going through archives to find, analyse and then illustrate the relationship between humans and plants, for example, how we give flowers to each other. By scrutinising how those perspectives are depicted in the archive films, I wanted to further define the plant and build something around those insights. The process with archive imagery was mainly led by improvisation — I did not know what I would find there and I had no precise script in that part. The idea of reframing the images came in the process of sitting in the archives and editing the film.

“The connection between knowing and not knowing is very interesting”

Largely speaking, as the title of the film also hints, it all comes down to memory and the active process of remembering. During the materialist practices such as archive research, I came close to the idea that we are not alone in this moment of history — there is a constant continuity in us. Through our film, we have tried to value life, to remember who we are, where we come from, and to express it through the epigenetic memory of the Thale Cress plant, which passes down from one generation to another. The past, as it guides us to the future, in a way, can become a place of negotiation. In the film, we strove to imagine and construct a different future and to express it through images. For me, the lengthy process of documentary filmmaking is a negotiation between inside and outside — a place for rebirth. I wanted to explore what happens when you spend a considerable amount of time with plants, for instance, to enjoy days in their presence or even to spend years with them. This aspect of listening to them, of coexistence, has been a process of negotiation between many factors of filmmaking.

TJ: Now, let me explicitly concentrate on the connection between bodily movements and the aspect of memory in the way in which the body inherits and preserves a primordial memory and knowledge. How are you working with the aspect of bodily memory in your practice?

TL: The Butoh performer featured in the film has already been practising the dance for thirty years. He has taught me a lot about this fantastic practice, which initially comes from a belief in the animistic character of things, that everything has a soul, even a chair, a table, basically any creature you can name. I felt that I had found the right person to do the film with. We did not shape the choreography beforehand; instead, through improvisation, the performer gave something new to the film. I consider him and the movement of the body as a gift for the film. While observing the bugs in a bug school, in which I was also a student, we carefully watched how bugs moved and be-haved. The performance of the transformation from human to insect is a paradox but I wanted to have a person who would believe in it and who could do it. In these eco-catastrophic times, it is really important to reach out to other species and learn compassion in the process. Through my film, I wanted to bring humans and insects closer to open up a different world and ask the question: What can we learn by being together with these creatures? Butoh and other meditative practices are great tools to challenge, educate and reveal ourselves — to experience what is inside our bodies.

JH: I think the body is a place of emergence of epigenetic memory. Thus, through different bodily practices, we can give space for history to reveal itself. The film, with all its complex layers, can be a perfect medium for such emergence. The insight into the evolution of epigenetic cells is essential for the performance of dancers in the film. They follow the practice called ecosomatics, which investigates the history of life and evolution in the human body. I suggested to them that we collaborate, and we worked on constructing the scenes together. Through bodily movements, the dancers try to reveal the embodied history of humanity.

TJ: The thematic angles, ideas and practices we have discussed so far also affect the cinematic language: narrative, visuality, performance, camera angle, focus and movement, lighting, sound and music, editing and rhythm. In that regard, both films share some experimental similarities in order to reveal the world that is invisible to the human eye. What is your approach to the cinematic image as such?

TL: The film envelopes several different worlds and perspectives. First, in the world of insect enthusiasts, the sequence resembles a familiar documentary film setting. However, towards the end, one might realise that the camera retains an unusual distance from the bug enthusiasts — human faces are not in evidence in the film. About the second phase, which is the world of the bugs, I actually had a dream. I dreamt that I made this film. While watching insects on a dark background, which was a really long and boring scene in the film, people were falling asleep in the theatre. I realised that I wanted to do it in exactly this way! In the process of filming, I wanted to flee from the visual language of popular nature documentaries — mostly made in studios but imitating the natural habitat of the insects. In our case, we built a studio in the garden not to pretend to be in nature, but to protect and avoid harming the endangered species we had. We managed to do everything correctly, and after shooting, we took them back to where they had come from. I think the dark background in the film serves as a convenient technique to observe the insects exactly as they are. The third sequence at the end of the film is inspired by a utopian novel written by one of the bug enthusiasts. In that novel, a woman gives birth to a True Bug. I was enchanted by the novel and wanted to create a future utopia in which the insects are becoming more similar to humans. The film is all about opening up different worlds and giving viewers the freedom to find their own way of observing them.

JH: In my case, the idea of the first image was born while listening to the rough sketch of the composition created by Sampo Kasurinen — the composer of the film. Eyes closed, we were listening to it and the music brought the image to me. Even though the film is born via inner sensations, it is based on the knowledge we acquire from the outer world: researching the natural habitat of the plant, retrieving information from scientists and gathering both visual and textual materials. And then there are elements which, based on this knowledge, we invent artistically. In this sense, image-producing is a dialogue between worlds of the inside and the outside.

As for microscopic images and scenes, we were able to produce them solely with the help of technology which, of course, is limited to the technical possibilities. Despite that, for me, the camera is a magical machine — expanding the field of vision to see things invisible to the naked eye. Once machine vision intertwines with human perspectives and aesthetic callings, we receive something very interesting.

TJ: In times of deep environmental crisis and precarity, social injustice linked to race, class or gender, extinction of species, issues of local and indigenous populations and so forth, do you think we are witnessing a shift in cinema that might open up new perspectives, potentialities and worldviews?

TL: Even though the process is quite slow-paced and discussions such as this are very rare in the contemporary film industry, I hope we are onto something here.

JH: I also believe that art carries political potential. It can be transformative, not in the sense that it is supposed to heal us, but that the world itself is healing. There is always a search for something new which, in my view, should not aim to colonise, but should attempt to reconnect and negotiate with the world. The responsibility, principally, also lies on the side of the industry and the values and possibilities it provides.

All in all, I think the connection between knowing and not knowing is very interesting. I still have a feeling that there is a mystery occurring around these plants and, of course, around all nonhuman species. They might be coming closer to us but there is also an insuperable distance — the distance that needs to be respected. Isn’t it fascinating to experience this being together? How do we share life? How should we proceed to reestablish a long-lost connection?

Special thanks to Tina Jelia.